Saturday, December 09, 2017

Herriman Saturday

June 5 1909 -- A concerned citizen, apparently not a cat fancier, has petitioned the city council to institute a tax on cats ... well, what he really wants is licensing, but Herriman and the news writer are happier categorizing it as a tax.

Labels: Herriman's LA Examiner Cartoons

Friday, December 08, 2017

Wish You Were Here, from Kin Hubbard

In 1907 the International Postcard Company issued a set of Abe Martin postcards. Hubbard's feature was only three years old at this time, running in the Indianapolis News. As best I can guess, they just used existing Abe Martin sayings, because few of them are really suited for use on a postcard (the above being an example of that).

Labels: Wish You Were Here

Comments:

The "Card Club" referenced would be, judging from the confiscated items, a ladies' house party social function where they'd play games like Whist for prizes. The humor of the situation is that said constable is the law man of such a backward hick town that this raid is as close an approximation as could be managed to a city version where full scale, big-bucks gambling takes place

Post a Comment

Thursday, December 07, 2017

King News by Moses Koenigsberg: Chapter 14 Part 1

King News by Moses Koenigsberg

Published by F.A. Stokes Company, 1941Chapter 14

The Magic Back of "The Funnies" (part 1)

link to previous installment link to next installment[I'll be offering some footnotes for the material in this chapter. They are numbered in red, and the footnotes will be found at the end of the post. -- Allan]

Newspaper Feature Service, Inc. was the first independent syndicate organized to supply a complete budget of features to seven day-a-week publications 1. Its program met a somewhat mixed reception. Not a few editors resented the newcomer. They viewed its parent purpose as an invasion of their individual prerogatives. To begin with, their pride balked at a technique that “lowered them to the plane of ‘boiler plate sheets.’ ”2 The phrase bore reference to hundreds of dailies and weeklies made up with patented stereotype shells shipped from central points in their respective sections.

There was nothing despicable about the mechanical ingenuity of this system. The implication of contempt lay in the use of matter prepared in such form as to preclude editorial revision. The “boiler plate,” except for being sawed up, must be used as received. There were no facilities for textual amendment. These conditions also applied to the papier-mâché matrices in which Newspaper Feature Service incorporated the bulk of its output. Apprehensive executives considered their dignity only a part of the professional domain under attack. They visioned the involvement of economic factors. They believed their earning power was gauged by the relative proportions of the printing space over which they exercised full control. They feared that every column withdrawn from their area of authority would reduce their rating. It was a depletion of sovereignty. Disparagement of regular elements, created outside the orbit of their direction, varied with the imagination of these critics. Most devastating was the allusion “canned junk.” Package goods had not yet risen much above the standing of patent medicines. “Handmade” continued as a hallmark of superiority. And many a managing editor refused to classify material appearing in his editions as “handmade,” unless it had passed through his fingers in every stage from conception to publication.

To overcome this prejudice was more difficult than to gain the approval of another but much larger group of editors dominated by journalism’s abiding passion for “the latest and best way.” To them, syndication spelled the promise of a limitless auxiliary force. Its processes were still in the formative stage. Eventually, it evolved into the heaviest ordnance used for the capture of newspaper readers. Providence timed my entrance into this special arena at a most opportune juncture. In the year 1913, the list of daily publications in America reached its maximum—2,622. Of these, only a scant 800 were equipped with stereotype plants for the handling of matrices such as were supplied by Newspaper Feature Service. But this 30 percent embraced more than four-fifths of the 28,000,000 aggregate circulation.

Forty-odd syndicates were in existence. Fully half struggled along on a hit-or-miss basis. None of the managers had a background of thorough newspaper training. So, the success that came to me in this field during the next fifteen years was attributable in part to the quality of competition I encountered. It was my fortune to enroll a clientele with the largest reading circle to which an identical budget of features had yet been presented. The total ultimately exceeded an average week-day distribution of approximately 18,000,000 copies.

It would have been impossible to attract and hold such a volume of popular interest without the collaboration of an extraordinary assemblage of talent. A cavalcade of genius swept me onward in the galloping advance of syndication. To that brilliant array of artists, writers and editors must be assigned a considerable share in shaping the trend and projecting the spirit of the American press. Their roster included all the luminaries of the Hearst constellation. No privilege ever accorded to me is so rich with stimulating memories as their comradeship. Their contributions to newspaperdom marked a climactic phase of the evolution of the syndicate.

The infancy of that institution has been recited by a number of chroniclers, but its adolescence and maturity have engaged only the superficial attention of historians.3 That is readily explainable. The phenomena of this branch of journalism seldom emerge into full view. They fit so intimately into the mesh of production as to remain—except to those directly concerned— practically indistinguishable from the collateral routine. Ordinarily, they escape the understanding of the detached observer. Often their complexities baffle the insider.

Once it became advisable for me to make a thorough survey of these obscurities. The reactions of the reading public were especially significant. The syndicate was practically an undefinable entity to 90 percent of newspaper buyers. Not one out of ten paused to consider the difference between articles and drawings that originated with the publication’s regular staff and those that were obtained from outside agencies. There was little inclination to ponder the diversity. In that indifference lay one of the secrets of feature fecundity. It let down editorial bars, permitting an unrestricted range of acceptance.

In the quarter of a century following the inauguration of Newspaper Feature Service the number of active syndicates increased more than 300 percent. And this was in the face of a continuous decrease of buying units. The 2,622 dailies of 1913 had fallen to fewer than 2,000 in 1941, a decline of more than 23 percent. Continuous growth of a supply depot, in the face of a steadily shrinking market, remained for years one of the anomalies of syndication.

It was not until the 1880s that the term “syndicate” won preference as a description of the form of journalism which the word has since continued to denote. Roughly, it covers any centralized traffic in matter desirable to publishers. Specifically, it signifies the acquisition and sale of rights to reproduce for publication the works of authors and writers. That seems a simple formula. Actually, its threads run through nearly all the editorial convolutions of mass circulation.

|

| Early web press |

The revolutionary effects in various branches of the printing art, toward the close of the nineteenth century, combined to set out the 1890s as the dynamic decade of newspaperdom. Challenging coincidences marked the completion of inventions that had been in varying stages of development. The ’80s presented experimental models. The ’90s brought widespread installation of the finished implements. It was a spectacular sequence. In the forefront were the web press and the typesetting machine. Together, they gave to speed the captaincy of the craft. It multiplied production. It made possible the inclusion of today’s news in today’s editions in the brief time intervening between the origination of fresh intelligence and the homeward dispersal of the buying public. It was the charter of the large circulations of afternoon dailies.

Equally impellent to the forces of journalism was the advent of photo-engraving. No other adjunct of the newspaper page has exceeded its power to attract and hold readers. Its potency sharpens the controversy over its origin—whether the process was first perfected by S. H. Morgan in the New York Daily Graphic in 1880, by G. Meisenbach in Munich in 1882, or by Frederick E. Ives in Connecticut in 1885.4 Yet the substitution of the halftone etching for the chalkplate was dilatory. The need for technical training of local crews retarded the change.

This transformation from line drawings to camera images was still under way when another sensational advance stirred the publishing guild. It was the printing of multiple colors on the same page on a web press. That was a memorable feat of mechanical engineering. It was accomplished when four curved plates, whirling on separate cylinders, at hundreds of revolutions per minute, impressed their raised surfaces with pinpoint accuracy in an identical space on a fleeting sheet of newsprint, the web from which the press derived its name.

From this mechanized magic emerged the Sunday comic page. That infant prodigy might be termed the first progeny of a union of expedience. The color-press—pride of many long-deferred hopes—faced for a while a dilemma like that of a bedraggled bride waiting at the church. The trouble arose not from the dereliction of a groom, but from indecision concerning him. Like a parent vacillating between suitors for his daughter’s hand, the editor wavered in the selection of a medium for the output of the pressman’s latest marvel. There was pointed occasion for his hesitation.

It was at the peak of the mauve influence. Certain statutory crimes were less abominable in that generation than public offenses against prevailing taste. Mere novelty in itself has always been disturbing to some readers. In the ’90s it would be more than a mere novelty to splash primary hues where only monotones had previously appeared. Then, there were subjects to which treatment in colors might lend a false sensationalism. These surely should be avoided. A blunder with this innovation might prove disastrous.

There were two men in America for whom these considerations bore unique significance. One was Joseph Pulitzer; the other, George Washington Turner. Once associates, they had become enemies. Several years before, Turner quit the business of selling firearms to attach himself to the New York World. He won Pulitzer’s complete confidence. He was appointed general manager. In 1891, he left to assume charge of the New York Recorder, the daily behind which stood for a spell the cigarette millions of the Duke family. Turner took with him a comprehensive knowledge of Pulitzer’s plans. Among these was a pet project to perfect a chromatic printing device with which a Parisian inventor had been experimenting.

In the winter of 1892-93, Carvalho, then Pulitzer’s general manager, learned that R. Hoe & Company were erecting a press especially designed for Turner. It would apply red, blue and yellow inks, singly and in combinations, to the same page. Carvalho managed to get a peep at the contrivance. He saw enough from which to draw a rough sketch. Within a few hours, Walter Scott & Company were engaged in a construction race with their Hoe Company rivals. During the machine-building contest, staff meetings canvassed the best vehicle with which to parade the forthcoming victory of the graphic arts. Pulitzer himself terminated the discussions on the World. He ordered that the new press turn out facsimiles of famous paintings in the leading galleries of Europe.

Turner won the machinery duel. His press was delivered seven days ahead of Pulitzer’s. But the Recorder extracted more embarrassment than advantage from this victory. Its first four-color work appeared in the edition of April 2, 1893. The results were execrable. During the next twenty months—until regular weekly production began on December 9, 1894—chromatic printing was presented by the Recorder in only three issues, June 18, July 2 and August 20, 1893. In each of these the chief feature was a page entitled “Cosmopolitan Sketches—Annie, the Apple Girl.” It was a rather sad series.5

Seven months passed before the Pulitzer machine was put into production. The Recorder was furnishing valuable lessons in what to avoid. The World made several unsatisfactory trial runs. Pulitzer’s plan to duplicate famous paintings went awry. The reproductions were atrocious. A jury of critics, invited to comment on the enterprise, denounced it. Their artistic sensibilities were jarred. They grieved over possible harm to youthful readers. Such distortions of classic art could scarcely fail to unbalance appreciation of the masters. The edition was killed on the press. Copies of women’s gowns were next tried. The outcome was equally displeasing.

At last, on November 19, 1893—one year earlier than the date commonly accepted—the World issued its first colored supplement. The front and back pages respectively showed St. Patrick’s Cathedral at nine-o’clock mass and a Saturday-night scene at Atlantic Garden. Inside, in black and white, were panels culled from Die Fliegende Blaetter, Punch, Truth and other humorous periodicals. The printing disgusted Pulitzer. He shut down the apparatus to which he had looked for a captivating triumph. For nine months, the “wonder job” of the Walter Scott & Company shops stood idle in the New York World plant.

At this point, it becomes necessary to set forth the fallacy of a popular tradition. Contrary to a general notion, the colored comic did not issue from a genius for humor. It was born, not in a flash of afflatus, but in the travail of editorial minds straining to solve a problem. It was the answer to a mechanical conundrum. It is in no light spirit that the authenticity is here denied of a shrine at which millions have made sentimental obeisance. The genesis of a great social influence must not be lost in apocryphal incunabula. Posterity will be entitled to an accurate accounting of such a distinctive heritage as “the funnies.” It might guide the historian to a hidden bridge—the link between the quick laughter and the sober purposes of a strong people. It may bore the aesthete, but it should kindle the philosopher.

The newspaper comic has been an organ of modern culture. A great muscle that flexed the spirit while it quickened the pulse, it has been a powerful determinant of national character. It has sown cheerfulness, it has put to scorn the narrowness of little men; it has discredited the defeatist; it has lifted the heart and broadened the vision of numberless seekers for a smile; it has spread optimism by whetting the eagerness to live; it has promoted realism through disillusionment; it has kept America face to face with itself. Its opulent contributions to lingual imagery are appreciated even by some of those who refuse to find delight in the drolleries of such creations as Barney Google, Mickey Mouse, Joe Palooka, Li'l Abner, Freckles and his Friends, Katrinka, Popeye the Sailor, Blondie, and The Gumps.

Several of Pulitzer’s lieutenants felt that it would be flying in the face of providence to abandon the new machine and thus neglect the latest advance in the making of newspapers. One was General Manager Carvalho. Another was the Sunday editor, Morrill Goddard, who had already shown evidence of the surpassing ability that was to establish him as an outstanding figure in journalism. Carvalho urged that the color press would redeem itself if supplied with suitable material. Goddard agreed. They argued that they had been on the right track, with the right engine but the wrong fuel.

Pulitzer was willing to be persuaded. Through the summer of 1894 a number of editorial conferences were held. Pulitzer studied reports of the debates. Goddard favored the use of comics. He pointed to the growth of Puck, Judge, and other weeklies devoted to pictorial humor. A majority of his colleagues clung to their preference for women’s gowns. As much by a process of elimination as by affirmative selection, Goddard prevailed. The summer passed before Pulitzer assented.

Here again we confront a myth that must be laid. According to popular legend, the World’s first comic supplement, published on November 18, 1894, introduced The Yellow Kid by Richard Felton Outcault—“the comic from which all other comics are dated.” That impish creature did not arrive on the scene until more than a year later 6. And then he was the product of a synthetic evolution. The truth about this celebrated figure deserves accurate recording. Not only was it recognized as the foremost exemplification of a new art, but it acted as the inspiration for a historic term—“yellow journalism.”

Outcault, a draughtsman on the Electrical World, had been recommended to Goddard by Walt McDougall. This was the McDougall who drew the first full-page comic printed in colors. Outcault was slow to appreciate the possibilities of the gamin on whose shoulders he climbed to fame. It is true that he included in most of the parties in his “Shantytown” sketches the urchin with one snaggled tooth in a one-piece costume which might have been euphemistically described as a nightgown. It is also true that this tad was always burdened with the same elephantine ears that fixed his identity in later pages. But the lemon-tinted habiliment that endowed him with both his name and his role was the work of outsiders. It was no phase of Outcault’s conception. Nor was it the result of a search for comic effects. Its origin was utterly remote from any fine impulse of artistry. It grew out of the use of vulgar tallow fat.7

Chemistry embraced one of the most vexatious problems in the early days of multi-color printing on a web press. Between the choice of satisfactory hues and the achievement of a clear imprint, many difficulties intervened. Each fluid pigment was disposed to bolt its reservation or to back up in perverse tackiness. The reds and blues were unruly enough; but the yellows were worse. Experiments were made with all sorts of binders and varnishes. The outstanding need was for an efficient drying formula. Animal fats were tried without end. Tallow fats came into favor to arrest the fugitive tints and to hold them in docile consistency. To get the fullest service from this coarse agent, its efficacy was directed against the most refractory of the inks. The tallow was set to manage the yellow.

Control of the results required constant observation over an adequate area of printing surface. This must be sufficiently extensive to demonstrate degrees of penetration and absorption, variations of evaporation under thermal and atmospheric changes, and emulsive and other irregularities which a clever pressman in that era could sense more readily than he could describe. Saalberg 8, foreman of the tint-laying Ben Day machines, picked the spot. It was the white space inside the outline garment worn by Outcault’s barefoot guttersnipe. When the “Hully gee!” brat next appeared he was clad in brilliant new raiment. It was the shade of a slightly bleached orange. It turned the wearer into The Yellow Kid. A moderately popular feature was thus transformed into a capital hit.

The furtive ways of life of Outcault’s roguish hero lasted four months. Up to then he had drifted through Hogan s Alley and Casey’s Alley, nameless and unattached, careless about his wardrobe accessories and obviously unaware of the spectacular future that awaited him. Once he was seen in a pair of boots too big for the corner cop. At another time he was clad in violent red. All this came to an end March 15, 1896. On that day, he donned the resounding yellow which he never thereafter discarded and with which he began his dual career seven months later. 9

Starting October 18, 1896, this enchanting street arab showed regularly for several years in both the New York World and the New York Journal. Outcault had joined the Pulitzer-to-Hearst gold rush recounted on an earlier page. He installed en masse in the Journal the mirth-making denizens of “Shantytown.” The flavor of this epochal event is preserved in the announcement made by the Hearst paper on October 17, 1896, as follows:

AH! THERE! THE YELLOW KID

TOMORROW! TOMORROW!

An expectant public is waiting for the “American Humorist,” the NEW YORK JOURNAL'S COMIC WEEKLY—EIGHT FULL PAGES OF COLOR

THAT MAKE THE KALEIDOSCOPE PALE WITH ENVY.

Bunco steerers may tempt your fancy with “a color supplement” that is black and tan—four pages of weak, wishy-washy color and four pages of desolate waste of black.

But THE JOURNAL'S COLOR COMIC WEEKLY! Ah! There’s the diff!

EIGHT PAGES OF POLYCHROMATIC EFFULGENCE THAT MAKE THE RAINBOW LOOK LIKE A LEAD PIPE.

That’s the sort of color comic weekly that the people want; and they shall have it.

This advertisement is offered as a tonic for the sophisticated reader. It should be observed that the notice dwelt not so much on the goods to be delivered as on the package in which they would be wrapped. It promised more in exciting colors than in exciting comedy. Not a few publishers later adopted this standard of values. They could see the reds, blues and yellows with the naked eye. It required something beside optic equipment to see all the humor. This psychology was profitably employed for years by a Philadelphia syndicate. 10

It would be misleading, however, to consider the New York Journal's ballyhoo in that category. Hearst was playing a sure thing. He knew his press could print more colors on more pages than was possible with Pulitzer’s machine. Also, the most noteworthy item of information—the coming of The Yellow Kid— involved a ticklish fact. The feature was not to appear exclusively in the New York Journal.

The New York World, having copyrighted Outcault’s Shantytown characters, assigned a talented illustrator to continue its own series without interruption. His page was richer in pictorial than in humorous content. The drawings were strangely dissimilar to the studies in oil which leading museums exhibited a quarter of a century later from the brush of the same artist, George B. Luks.

|

| Ervin Wardman |

In his next creation, Outcault lifted the plane of his humor from the slums to the walks of the well-to-do. He brought forth a mischievous specimen of privileged youth. Counterpart of Little Lord Fauntleroy, this new star of the funnies, Buster Brown, imparted a distinctive tinge to American boyhood. No matter what may have been his influence upon the moods, his sway over the modes of his generation was immense. He shuffled the fashions of juvenile apparel. No detail of his attire escaped coast-to-coast imitation. Twenty years after his disappearance from newspaper circulation, manufacturers were still distributing “Buster Brown” articles of clothing under royalty licenses.

Outcault held a unique position in the world of comic art. He alone achieved two “double runs.” The Yellow Kid's feat of showing simultaneously in rival newspapers was repeated by Buster Brown. Outcault left Hearst to join James Gordon Bennett on the New York Herald in 1897. It was five years later that he brought out Buster Brown. The feature won a livelier appreciation from the readers than from the managers of the Herald. Outcault, demanding an increase of salary, received, as he afterward described it to me, “the age-old but none-the-less too previous horse laugh.”

E. W. Reick, the managing editor, was genuinely astonished at the nerve of Dick Outcault. This fellow evidently considered himself indispensable. He asked a higher rate of compensation than was paid to his fellow-worker, Winsor McCay. It happened that Reick was partial to McCay’s Little Nemo and Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend. But he thought $150 a week was liberal recompense for any pen-and-ink artist. Dick wanted more than that. Reick scoffed at his threat to resign. Copyright lawsuits between Bennett and Hearst corporations followed Outcault’s return to a prodigal son’s welcome on the New York Journal.

The final decision has since served as a judicial milestone. The Herald’s ownership of the Buster Brown series was confirmed. On the other hand, the decree protected Outcault against any abridgment of his right to work. He was at liberty to carry on with the children of his brain and hand. So he ushered the entire cast of characters into a Sunday page of the New York Journal. Debarred from the label Buster Brown, the Hearst paper used the caption Buster and Tige. An earnest young man, William Lawler, bound to slavish imitation of the originator, kept the feature going in the Herald under its initial title.

Meanwhile, the colored comic supplement had captured the ascendency that it continued to command. Publishers ranked it as their leading Sunday circulation “puller.” Incidentally, it was their most expensive section. Its cost per page was a great deal more than any other part of the paper. But the results would have warranted even a higher price.

In reviewing Outcault’s career, we find a perspective of the early stages of syndicate development. Also, we note conditions that qualified the making of newspapers for a number of years. Reick’s treatment of Outcault typified a considerable group of editors. Endowed with ample capacity for the handling of news, they go astray in the field of features. They seem unable to appraise either the potential or the immediate values of amusement elements.

It is a mistake to assume that they lack a sense of humor. Instead of a deficiency, there may be too sharp a discrimination, particularly where personal preferences have been cultivated. Funnies wilt in the chill of a special taste. Prejudices of the palate are no more helpful in compiling a restaurant bill of fare than crotchets are useful in selecting a menu of comics for a daily.

Reick’s willingness to lose Outcault meant readiness to rely on a substitute for a star. That was a common trait among executives. Capitalizing newsprint personalities was still an infant industry. The anatomy of a comic was an inchoate mystery. Its physiology was terra incognita. Reick believed there would be only a negligible difference between Outcault’s Buster Brown pages and those produced by his successor. A number of his compeers— clients of the New York Herald syndicate—shared in this judgment. Apparently, they were unacquainted with the parallel of “the perfect violin.”

That analogy long served as one of my favorite illustrations of counsel for aspirants to journalistic primacy. It postulates two virtuosi rendering an identical composition. Both play every note in the score. They start and finish at the same time. Each gives a technically flawless performance. Yet one is lionized by audiences paying $5 a seat, while the other earns scarcely a pittance above the labor union’s scale. The demonstration is completed by interchanging the violinist’s bow and the comic artist’s pen.

When Outcault joined Newspaper Feature Service in 1913, he had shaken off all imitators. He fell in heartily with an elaborate promotion project. It was to establish Buster as the permanent leader of a section of Young America. A recital of the plan and its outcome is offered here as a solemn service. The record merits emphasis whenever soi-disant statesmen gather to ventilate their wisdom in matters of war.

A “Buster Brown League” was formulated, open to every boy and girl in the country. The token of membership was a button designed by Outcault. It symbolized faith in an informal philosophy based on Buster’s resolutions. One of those pledges appeared in each Sunday page. It was the epilogue of a hilarious adventure. It was inscribed on a pillow tied around Buster’s person at a position explanatory of his penitent spirit. It epitomized a reason for better behavior. Here are three specimens:

Resolved—That I must have sleep if I have to stay up all night to get it. The peace that passeth all understanding comes with honest, healthy sleep. You can’t buy it. If you could, I’d want to own a sleep store.

Resolved—-That the best policy is to be honest. But don’t let anybody know it. . . . People won’t believe you; but it makes you happy and prosperous to be honest and you’re not afraid of the dark.

Resolved—That truth is all right if used at the right time and place. . . . Tact and truth are two different things. Tact is the polite name for lies you have to tell sensitive people.

A preliminary order for 3,000,000—based on a total of 7,000,000 —membership insignia was placed with the Whitehead & Hoag Company of New Jersey. Arrangements for their distribution and for measures of organization maintenance were perfected with newspapers using the Buster Brown feature. Editors assured me of their cordial approval. Their circulation managers were highly enthusiastic. Public announcement was to be made at a formal function in Washington. This was to be attended by a dozen men and women conspicuous in the movement to modernize the education of youth. In addition, letters were addressed to a carefully chosen list of 250 leaders of the then vigorous “uplift trend.” The recipients were invited to serve as councilors and to authorize for publication their endorsement of the Buster Brown League. The result astounded me.

The plan, which Outcault had flatteringly hailed as “a meteoric idea,” was twisted into a knot. The meteor turned into a blackout, not because it was tied to the tail of a comic, but because it scorched the tail of a national behemoth. The Cerberus of pacifism— personified by an impressive circle of ministers, philanthropists, authors, sociologists and clubwomen—growled disapproval. Tart notes of remonstrance reached me from all directions.

Jane Addams, of revered memory, head of Chicago’s Hull House, emphasized both displeasure and sorrow. Censorious comments came from Judge Ben Lindsey, Anne Morgan, Rev. Messrs. C. H. Parkhurst and Thomas F. Dixon, Carrie Chapman Catt, Samuel Gompers, Joseph W. Folk, Gertrude Atherton, Clarence S. Darrow, United States Senator George W. Norris and a number of notable “uplifters.” More astonishing than the unanimity of these rebuffs was the unity of reasoning that prompted them.

Consolidating the messages in a composite communication, while retaining a bit of the emotional phraseology, would have produced something like this: “We have gone through a generation of peace-making. We are at the threshold of the brotherhood of man. We have reached this high point of human development after sustained research, thinking and planning for permanent peace. We have found that the most fertile field for the seeds of war lies in the regimentation of youth. We have uniformly opposed any and all attempts to regiment the young. Now, when we have come so far away from that field of deadly ferment, you ask that we help you lead a return to the regimentation of youth. It is a vicious proposal that calls for vigorous opposition.”

Suspicion, partly engendered perhaps by disappointment, prompted an inquiry into the genuineness of these sapient deliverances. Charles V. Tevis, my assistant, was directed to interview a number of the writers. His report left no doubt about their sincerity. That was in April, 1914. Three months later came the outbreak of the World War. The Buster Brown League passed on, ephemeral victim of a timeless heresy. And that was twenty-five years before appeasement took its stand beside pacifism.

Footnotes

1 - As unlikely as this claim seems, I cannot refute it. Koenigsberg's listed conditions are (1) the syndicate cannot be remarketing material used by a parent newspaper, and (2) the material offered must include both daily material and Sunday material. McClure and World Color Printing had both dabbled a bit with offering dailies by this time, but their offerings were sporadic, so I'm not going to count them. NEA and International Syndicate, on the other hand, offered daily material only. Pretty much every other player was associated with a home paper.

2 - Boilerplate syndicate material was very well-known, popular and accepted by 1913. It seems very doubtful that Koenigsberg got any push-back. This is fairly typical Koenigsberg, trying to build himself up by belittling others.

3 - By the time Koenigsberg was writing this material, syndication history had been explored in a grand total of one slim publication (which you will find reprinted in full here on Stripper's Guide). Journalism histories had (and even continue to have) a habit of ignoring syndication, despite it being in many ways the brick and mortar that holds together most modern American newspapers.

4 - The halftone process does indeed have a number of 'inventors'. Oddly, Koenigsberg doesn't mention the leading contender, Frederic Eugene Ives, whose process supposedly became the de facto standard not only for newspapers but most other printing. Perhaps he is seeking to give the mantle to the newspaper press technicians who actually put the concept into use in the real world?

5 - While the New York Recorder was indeed the first paper in New York to do four-color printing, the Chicago Inter-Ocean was turning out full-color material starting almost a full year earlier.

I have a bound volume of the 1893 Recorder where I unfortunately cannot currently reach it, and my recollection is that their experiments with color were primarily in the genre of ladies fashions along with the art reproductions whose printing quality was so infamously awful. I do not, however, recall a continuing titled series like Koenigsberg seems to be describing.

6 - Not quite. The first identifiable Yellow Kid, though at the time wearing a blue nightshirt, was in May 1895.

7 - Koenigsberg is about to relate the tale of the Yellow Kid being a testbed for printing a large area of yellow. As can be plainly seen in these early comics sections, yellow was being used regularly and successfully long before the Kid was ever colored yellow (see here for samples). Unfortunately, this tall tale continues to be repeated in pop histories to this day.

8 - This is Charles W. Saalburg, star artist and technician of the Chicago Inter-Ocean color sections of 1892-4. He sometimes did apparently spell his name Saalberg.

9 - The date cited is actually the first time that Outcault wrote words on the Kid's nightshirt. He'd been in yellow for awhile before that.

10 - One has to wonder which Philadelphia syndicate Koenigsberg is insulting here. Frankly, the three major players -- the Inquirer, the North American and the Press, all had comics sections that were ripe for ridicule.

Chapter 14 Part 2 Next Week link to previous installment link to next installment

Labels: King News

Wednesday, December 06, 2017

Ink-Slinger profiles by Alex Jay: Hedrick

In the 1880 U.S. Federal Census, Hedrick was the youngest of three children. His father was a manager of an unspecified business. The family resided in East Carroll, Louisiana.

The Book of St. Louisans said Hedrick was educated at country schools in Louisiana and at public schools in Mineola, Texas, until 12 years old, and after that he was self-taught. Hedrick was a newsboy at 12, then a postal clerk at 14. In 1890, Hedrick was a contributor to the publications Louisville Courier Journal and Louisville Truth. A 1891 Louisville, Kentucky city directory had a listing for “Keene Hedrick”, a draughtsman at S.C. Gates, who lived at 1824 Brook.

Hedrick spent time in Texas as a railroad clerk in Mineola in 1891. He was a cartoonist for Dallas newspapers from 1892 to 1894 and later, in 1895, at the Houston Post. The 1896 Dallas city directory said Hedrick was a photo-engraver, an occupation mentioned in Cartoons Magazine, April 1917.

The Globe-Democrat in St. Louis, Missouri was Hedrick’s next stop from 1896 to 1903. Hedrick contributed illustrations to Harry B. Wandell’s One Purple Week; and Then— (1898).

Hedrick was in his mother’s household according to the 1900 census. The cartoonist resided in St. Louis at 1382 Lucretia Avenue. In the 1903 city directory, Hedrick’s address was 3502 Pine.

Hedrick married Mary St. Clair McCamish in Mineola, Texas, on December 10, 1903.

Hedrick was a member of the Single Tax League. A 1901 issue of the Single Tax Review reported this item: “T. K. Hedrick, the able cartoonist of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, and writer of the department in the paper called ‘The Echoes of the Streets,’ is a member of our league.”

After his stint with the Globe-Democrat, Hedrick was a freelance magazine writer and cartoonist. American Newspaper Comics (2012) said Hedrick produced Mister Hypo for the Globe-Democrat which ran it from June 4 to July 30, 1905.

In June 1904, Hedrick was one of the American Press Humorists at the St. Louis World’s Fair. A group photograph was published in the Inland Printer, August 1904.

In the 1908 St. Louis directory, Hedrick’s home was 5149 Ridge Avenue. The address was 1355 Clara Avenue in the 1910 census. Hedrick and his wife had two sons, Travis and Edward. Hedrick was a freelance journalist. According to the Chicago Tribune, August 11, 1935, Hedrick moved, in 1910, to Chicago and worked for the Daily News.

When Hedrick signed his World War I draft card on September 12, 1918, he was a resident of Chicago at 849 Lafayette Street. He was an editor employed by Victor Lawson. Hedrick was described as short, slender build with brown eyes and dark hair.

Two daughters, Mary and Ella, were listed in the Hedrick household in the 1920 census. The family of six resided at 5640 Kenmore Avenue in Chicago. Hedrick’s home in the 1930 census was the Hotel Broadmoor Apartment, 7606 Bosworth Avenue.

In 1921, the Bobb-Merrill Company published Hedrick’s book, Orientations of Ho-Hen.

New York Tribune 4/9/1922

—Alex Jay

Labels: Ink-Slinger Profiles

Comments:

Good afternoon. I was delighted to come across this post as TK Hedrick is my great grandfather. In addition to his work as a cartoonist for the Chicago Sun Times, he was also an editor of books about and close friends with Carl Sandberg. He also wrote a book.

Post a Comment

Tuesday, December 05, 2017

Ink-Slinger Profiles by Alex Jay: Don/Dom J. Lavin

Information regarding Lavin’s education and art training has not been found. According to a 1900 Chicago city directory, Lavin was an artist residing at 5660 Madison Avenue. In the 1901 directory Lavin was at the Chicago American, which became the Examiner in 1904, and lived at 648 65th Street.

The Cook County marriage index said Lavin married Amelia Esther Preston in Chicago on April 17, 1901.

Lavin was with the Examiner when he exhibited forty works in the First Annual Exhibition [of the] Newspaper Cartoonists’ and Artists’ Association at the Art Institute in May 1905. In the Chicago Tribune, March 28, 1949, Frank King recalled when Lavin hired him to work in the Examiner art department (see page 14).

The Tribune, September 30, 1909, reported a tragic accident at Lavin’s home (see column 3).

The 1910 census did not record Lavin’s occupation. He and his wife had an eight-year-old son, Robert, and employed a housekeeper. They resided in Chicago at 6510 Ingleside Avenue.

Lavin illustrated for a number periodicals including Wayside Tales, The Idler, The Day Book, and The Green Book.

Lavin was associated with the Federal School of Applied Cartooning and Federal School of Commercial Designing.

Lavin was an instructor at Chicago's American Academy of Art where one of his student’s was William Juhre.

During his time at the Tribune, Lavin was an avid golfer as noted in The Scoop and The Fourth Estate.

On September 12, 1918, Lavin signed his World War I draft card. He was art editor at the Tribune. He was described as tall, medium build with gray eyes and brown hair.

In 1919 Lavin left the Tribune and joined the the Charles Daniel Frey Company.

Tribune 3/21/1919

Lavin’s address was unchanged in the 1920 and 1930 censuses. He worked in advertising. Advertising Arts and Crafts (1927) had this listing for him, “Lavin, Dom J., 63 E. Adams, Wab 6480 Chicago, Ill.”

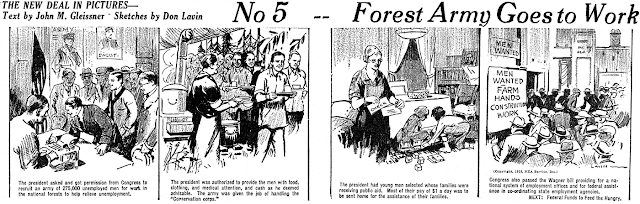

Lavin drew The New Deal in Pictures for the NEA which ran it from July 27 to August 10, 1933. American Newspaper Comics (2012) said Lavin drew Do You Know? for the Chicago Defender. The panel ran from April 4 to June 6, 1936.

At some point Lavin moved to California. The 1940 Paseadena city directory listed commercial artist Lavin at 335 Parke and the name of his second wife, Hazel. Cartoonist Lavin was at 262 Palmetto Drive in the 1947 directory. The Pasadena directories from 1949 to 1956 had Lavin’s address as 364 Rosemont Avenue.

Lavin passed away June 14, 1958. His death was reported in the Independent Star-News (Pasadena, California), the following day.

Lavin drew The New Deal in Pictures for the NEA which ran it from July 27 to August 10, 1933. American Newspaper Comics (2012) said Lavin drew Do You Know? for the Chicago Defender. The panel ran from April 4 to June 6, 1936.

At some point Lavin moved to California. The 1940 Paseadena city directory listed commercial artist Lavin at 335 Parke and the name of his second wife, Hazel. Cartoonist Lavin was at 262 Palmetto Drive in the 1947 directory. The Pasadena directories from 1949 to 1956 had Lavin’s address as 364 Rosemont Avenue.

Lavin passed away June 14, 1958. His death was reported in the Independent Star-News (Pasadena, California), the following day.

Don Lavin, 83-year-old veteran newspaper artist and contributor to The Independent Star-News, died yesterday at a Pasadena rest home.

Lavin, who resided at 364 Rosemont St., Pasadena, was admitted to the home four weeks ago of treatment of a heart condition.

A native of San Francisco, Lavin was head artist for the Chicago Tribune for many years before coming to California. While here, his work appeared from time to time in this newspaper.

He is survived by a son, R. Preston Lavin, of Chicago, and a close friend, Ernest Spaulding of Pasadena.

Funeral services are pending at the Lamb Funeral Home.

—Alex Jay

Labels: Ink-Slinger Profiles

Monday, December 04, 2017

Obscurity of the Day: The New Deal in Pictures

The NEA syndicate would eventually become nearly constant purveyors of closed-end newsy comic strip series, but until the late 1930s, they were seldom offered. One of the earliest attempts at telling a news story through the comic strip format came in 1933, when they offered The New Deal in Pictures.

Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal programs were coming fast and furious, and the alphabet soup of new bureaus and programs was tough to keep up with. NEA's solution was to offer a short, punchy explanation of them all in the form of a comic strip series in thirteen daily installments.

The official running dates of the series, per NEA archives at the OSU cartoon library, are July 27 to August 10. However, as was often the case with these series, many papers ran them late, out of order or incomplete.

The text was written by John M. Gleissner, who was a Washington DC newspaper editor in the 1920s, and apparently then went to work for NEA. The art was by Don J. Lavin, whose biggest mark was as head of the Chicago Tribune art department in the 1910s. He did a little work for NEA between 1932-34, with this feature the only comic strip series. According to Alex Jay, his full given name was Dominic, which leads me to wonder if he is the same fellow who did Did You Know? for the Chicago Defender in 1936 as Dom J. Lavin, rather than his more typical 'Don'. Most likely he did, since Chicago seemed to be his home base.

Thanks to Cole Johnson, who supplied the sample strip ... probably with a clothespin on his nose as he scanned it, as he was definitely not a fan of FDR. Sadly I have lost any comments he made about the strip; I imagine he had a few bon mots to say on the subject of the New Deal.

Labels: Obscurities

Comments:

Judging from the memoirs of Herbert L. Block ("Herblock"), who was a staff editorial cartoonist at NEA in the 1930s, NEA (owned by Scripps-Howard) was generally a conservative place. Mildly surprising they would have a pro-New Deal strip.

Post a Comment